James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler | |

|---|---|

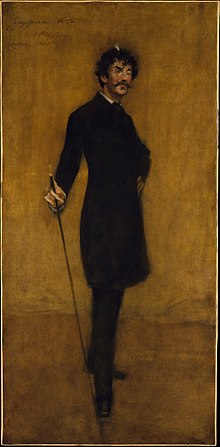

Arrangement in Gray: Portrait of the Painter (self portrait, c. 1872), Detroit Institute of Arts | |

| Born | July 10, 1834 |

| Died | July 17, 1903 (aged 69) London, England, UK |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | United States Military Academy, West Point, New York |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Whistler's Mother |

| Movement | Founder of Tonalism |

| Spouse | |

| Parents | |

| Awards |

|

James Abbott McNeill Whistler RBA (/ˈwɪslər/; July 10, 1834 – July 17, 1903) was an American painter in oils and watercolor, and printmaker, active during the American Gilded Age and based primarily in the United Kingdom. He eschewed sentimentality and moral allusion in painting and was a leading proponent of the credo "art for art's sake".

His signature for his paintings took the shape of a stylized butterfly with an added long stinger for a tail.[1] The symbol combined both aspects of his personality: his art is marked by a subtle delicacy, while his public persona was combative. He found a parallel between painting and music, and entitled many of his paintings "arrangements", "harmonies", and "nocturnes", emphasizing the primacy of tonal harmony.[2] His most famous painting, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (1871), commonly known as Whistler's Mother, is a revered and often parodied portrait of motherhood. Whistler influenced the art world and the broader culture of his time with his aesthetic theories and his friendships with other leading artists and writers.[3]

Early life

[edit]Heritage

[edit]James Abbott Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts on July 10, 1834,[4][5][6] the first child of Anna McNeill Whistler and George Washington Whistler, and the elder brother of Confederate surgeon William McNeill Whistler.[citation needed]

In later years, Whistler played up his mother's connection to the American South and its roots, and he presented himself as an impoverished Southern aristocrat, although it remains unclear to what extent he truly sympathized with the Southern cause during the American Civil War. He adopted his mother's maiden name after she died, using it as an additional middle name.[7]

New England

[edit]His father was a railroad engineer, and Anna was his second wife. James lived the first three years of his life in a modest house at 243 Worthen Street in Lowell, Massachusetts.[8] The house is now the Whistler House Museum of Art, a museum dedicated to him.[9] He claimed St. Petersburg, Russia as his birthplace during the Ruskin trial: "I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell."[10]

Whistler was a moody child, prone to fits of temper and insolence, and he often drifted into periods of laziness after bouts of illness. His parents discovered that drawing often settled him down and helped focus his attention.[11]

The family moved from Lowell to Stonington, Connecticut in 1837, where his father worked for the Stonington Railroad. Three of the couple's children died in infancy during this period.[8] Their fortunes improved considerably in 1839 when his father became chief engineer for the Boston & Albany Railroad,[12] and the family built a mansion in Springfield, Massachusetts, where the Wood Museum of History now stands. They lived in Springfield until they left the United States for Russia in late 1842.[13]

Russia and England

[edit]

In 1842, his father was recruited by Nicholas I of Russia to design a railroad in Russia. The Emperor learned of George Whistler's ingenuity in engineering the Canton Viaduct for the Boston & Albany Railroad, and he offered him a position engineering the Saint Petersburg-Moscow Railway. The rest of the family moved to St. Petersburg to join him in the winter of 1842/43.[7]

After moving to St. Petersburg, the young Whistler took private art lessons, then enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts at age eleven.[10] The young artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live models, revelled in the atmosphere of art talk with older peers, and pleased his parents with a first-class mark in anatomy.[14] In 1844, he met the noted artist Sir William Allan, who came to Russia with a commission to paint a history of the life of Peter the Great. Whistler's mother noted in her diary, "the great artist remarked to me 'Your little boy has uncommon genius, but do not urge him beyond his inclination.'"[15]

In 1847–1848, his family spent some time in London with relatives, while his father stayed in Russia. Whistler's brother-in-law Francis Haden, a physician who was also an artist, spurred his interest in art and photography. Haden took Whistler to visit collectors and to lectures, and gave him a watercolour set with instruction.[citation needed]

Whistler already was imagining an art career. He began to collect books on art and he studied other artists' techniques. When his portrait was painted by Sir William Boxall in 1848, the young Whistler exclaimed that the portrait was "very much like me and a very fine picture. Mr. Boxall is a beautiful colourist... It is a beautiful creamy surface, and looks so rich."[16] In his blossoming enthusiasm for art, at fifteen, he informed his father by letter of his future direction, "I hope, dear father, you will not object to my choice."[17] His father, however, died from cholera at the age of 49, and the Whistler family moved back to his mother's home town of Pomfret, Connecticut.[citation needed][18]

The family lived frugally and managed to get by on a limited income. His art plans remained vague and his future uncertain. His cousin reported that Whistler at that time was "slight, with a pensive, delicate face, shaded by soft brown curls... he had a somewhat foreign appearance and manner, which, aided by natural abilities, made him very charming, even at that age."[19]

West Point

[edit]Whistler was sent to Christ Church Hall School with his mother's hopes that he would become a minister.[20] Whistler was seldom without his sketchbook and was popular with his classmates for his caricatures.[21] However, it became clear that a career in religion did not suit him, so he applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where his father had taught drawing and other relatives had attended. He was admitted to the highly selective institution in July 1851 on the strength of his family name, despite his extreme nearsightedness and poor health history.[22] However, during his three years there, his grades were barely satisfactory, and he was a sorry sight at drill and dress, known as "Curly" for his hair length which exceeded regulations. Whistler bucked authority, spouted sarcastic comments, and racked up demerits. Colonel Robert E Lee was the West Point Superintendent and, after considerable indulgence toward Whistler, he had no choice but to dismiss the young cadet. Whistler's major accomplishment at West Point was learning drawing and map making from American artist Robert W. Weir.[20]

His departure from West Point seems to have been precipitated by a failure in a chemistry exam where he was asked to describe silicon and began by saying, "Silicon is a gas." As he himself put it later: "If silicon were a gas, I would have been a general one day".[23] However, a separate anecdote suggests misconduct in drawing class as the reason for Whistler's departure.[24]

First job

[edit]After West Point, Whistler worked as draftsman mapping the entire U.S. coast for military and maritime purposes.[25] He found the work boring and he was frequently late or absent. He spent much of his free time playing billiards and idling about, was always broke, and although a charmer, had little acquaintance with women.[26] After it was discovered that he was drawing sea serpents, mermaids, and whales on the margins of the maps, he was transferred to the etching division of the United States Coast Survey. He lasted there only two months, but he learned the etching technique which later proved valuable to his career.[20]

At this point, Whistler firmly decided that art would be his future. For a few months he lived in Baltimore with a wealthy friend, Tom Winans, who even furnished Whistler with a studio and some spending cash. The young artist made some valuable contacts in the art community and also sold some early paintings to Winans. Whistler turned down his mother's suggestions for other more practical careers and informed her that with money from Winans, he was setting out to further his art training in Paris. Whistler never returned to the United States.[27]

Art study in France

[edit]Whistler arrived in Paris in 1855, rented a studio in the Latin Quarter, and quickly adopted the life of a bohemian artist. Soon he had a French girlfriend, a dressmaker named Héloise.[28] He studied traditional art methods for a short time at the Ecole Impériale and at the atelier of Charles Gleyre. The latter was a great advocate of the work of Ingres, and impressed Whistler with two principles that he used for the rest of his career: that line is more important than color and that black is the fundamental color of tonal harmony.[29] Twenty years later, the Impressionists would largely overthrow this philosophy, banning black and brown as "forbidden colors" and emphasizing color over form. Whistler preferred self-study and enjoying the café life.[20]

While letters from home reported his mother's efforts at economy, Whistler spent freely, sold little or nothing in his first year in Paris, and was in steady debt.[30] To relieve the situation, he took to painting and selling copies from works at the Louvre and finally moved to cheaper quarters. As luck would have it, the arrival in Paris of George Lucas, another rich friend, helped stabilize Whistler's finances for a while. In spite of a financial respite, the winter of 1857 was a difficult one for Whistler. His poor health, made worse by excessive smoking and drinking, laid him low.[31]

Conditions improved during the summer of 1858. Whistler recovered and traveled with fellow artist Ernest Delannoy through France and the Rhineland. He later produced a group of etchings known as "The French Set", with the help of French master printer Auguste Delâtre. During that year, he painted his first self-portrait, Portrait of Whistler with Hat, a dark and thickly rendered work reminiscent of Rembrandt.[10] But the event of greatest consequence that year was his friendship with Henri Fantin-Latour, whom he met at the Louvre. Through him, Whistler was introduced to the circle of Gustave Courbet, which included Carolus-Duran (later the teacher of John Singer Sargent), Alphonse Legros, and Édouard Manet.[20]

Also in this group was Charles Baudelaire, whose ideas and theories of "modern" art influenced Whistler. Baudelaire challenged artists to scrutinize the brutality of life and nature and to portray it faithfully, avoiding the old themes of mythology and allegory.[32] Théophile Gautier, one of the first to explore translation qualities among art and music, may have inspired Whistler to view art in musical terms.[33]

London

[edit]Reflecting his adopted circle's banner of the Realism art movement, Whistler painted his first exhibited work, La Mère Gérard in 1858. He followed it by painting At the Piano in 1859 in London, which he adopted as his home, while also regularly visiting friends in France. At the Piano is a portrait composed of his niece and her mother in their London music room, an effort which clearly displayed his talent and promise. A critic wrote, "[despite] a recklessly bold manner and sketchiness of the wildest and roughest kind, [it has] a genuine feeling for colour and a splendid power of composition and design, which evince a just appreciation of nature very rare amongst artists."[34] The work is unsentimental and effectively contrasts the mother in black and the daughter in white, with other colors kept restrained in the manner advised by his teacher Gleyre. It was displayed at the Royal Academy the following year, and in many exhibits to come.[33]

In a second painting executed in the same room, Whistler demonstrated his natural inclination toward innovation and novelty by fashioning a genre scene with unusual composition and foreshortening. It later was re-titled Harmony in Green and Rose: The Music Room.[35] This painting also demonstrated Whistler's ongoing work pattern, especially with portraits: a quick start, major adjustments, a period of neglect, then a final flurry to the finish.[34]

After a year in London, he produced a set of etchings in 1860 called Thames Set, as counterpoint to his 1858 French set, as well as some early impressionistic work including The Thames in Ice. At this stage, he was beginning to establish his technique of tonal harmony based on a limited, predetermined palette.[36]

Early career

[edit]

In 1861, after returning to Paris for a time, Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. The portrait of his mistress and business manager Joanna Hiffernan was created as a simple study in white; however, others saw it differently. The critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary thought the painting an allegory of a new bride's lost innocence. Others linked it to Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White, a popular novel of the time, or various other literary sources. In England, some considered it a painting in the Pre-Raphaelite manner.[37] In the painting, Hiffernan holds a lily in her left hand and stands upon a wolf skin rug (interpreted by some to represent masculinity and lust) with the wolf's head staring menacingly at the viewer. The portrait was refused for exhibition at the conservative Royal Academy, but was shown in a private gallery under the title The Woman in White. In 1863, it was shown at the Salon des Refusés in Paris, an event sponsored by Emperor Napoleon III for the exhibition of works rejected from the Salon.[38]

Whistler's painting was widely noticed, although upstaged by Manet's more shocking painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe. Countering criticism by traditionalists, Whistler's supporters insisted that the painting was "an apparition with a spiritual content" and that it epitomized his theory that art should be concerned essentially with the arrangement of colors in harmony, not with a literal portrayal of the natural world.[39]

Two years later, Whistler painted another portrait of Hiffernan in white, this time displaying his newfound interest in Asian motifs, which he entitled The Little White Girl. His Lady of the Land Lijsen and The Golden Screen, both completed in 1864, again portray his mistress, in even more emphatic Asian dress and surroundings.[40]

During this period Whistler became close to Gustave Courbet, the early leader of the French realist school, but when Hiffernan modeled in the nude for Courbet, Whistler became enraged and his relationship with Hiffernan began to fall apart.[41]

In January 1864, Whistler's very religious and very proper mother arrived in London, upsetting her son's bohemian existence and temporarily exacerbating family tensions. As he wrote to Henri Fantin-Latour, "General upheaval!! I had to empty my house and purify it from cellar to eaves." He also immediately moved Hiffernan to another location.[42]

From 1866, Whistler made his home in Chelsea, London, an area popular with artists, firstly in Cheyne Walk, then an ill-fated move to Tite Street, and finally Upper Church Street.[43]

Mature career

[edit]Nocturnes

[edit]

In 1866, Whistler decided to visit Valparaíso, Chile, a journey that has puzzled scholars, although Whistler stated that he did it for political reasons. Chile was at war with Spain and perhaps Whistler thought it a heroic struggle of a small nation against a larger one, but no evidence supports that theory.[42] What the journey did produce was Whistler's first three nocturnal paintings (which he originally termed "moonlights"): night scenes of the harbor painted with a blue or light green palette.[citation needed]

After he returned to London, he painted several more nocturnes over the next ten years, many of the River Thames and of Cremorne Gardens, a pleasure park famous for its frequent fireworks displays, which presented a novel challenge to paint. In his maritime nocturnes, Whistler used highly thinned paint as a ground with lightly flicked color to suggest ships, lights, and shore line.[44] Some of the Thames paintings also show compositional and thematic similarities with the Japanese prints of Hiroshige.[45]

In 1872, Whistler credited his patron Frederick Leyland, an amateur musician devoted to Chopin, for his musically inspired titles.

I say I can't thank you too much for the name 'Nocturne' as a title for my moonlights! You have no idea what an irritation it proves to the critics and consequent pleasure to me—besides it is really so charming and does so poetically say all that I want to say and no more than I wish![46]

At that point, Whistler painted another self-portrait and entitled it Arrangement in Gray: Portrait of the Painter[47] (c. 1872), and he also began to re-title many of his earlier works using terms associated with music, such as a "nocturne", "symphony", "harmony", "study" or "arrangement", to emphasize the tonal qualities and the composition and to de-emphasize the narrative content.[46] Whistler's nocturnes were among his most innovative works. Furthermore, his submission of several nocturnes to art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel after the Franco-Prussian War gave Whistler the opportunity to explain his evolving "theory in art" to artists, buyers, and critics in France.[48]

His good friend Fantin-Latour, growing more reactionary in his opinions, especially in his negativity concerning the emerging Impressionist school, found Whistler's new works surprising and confounding. Fantin-Latour admitted, "I don't understand anything there; it's bizarre how one changes. I don't recognize him anymore." Their relationship was nearly at an end by then, but they continued to share opinions in occasional correspondence.[49]

When Edgar Degas invited Whistler to exhibit with the first show by the Impressionists in 1874, Whistler turned down the invitation, as did Manet, and some scholars attributed this in part to Fantin-Latour's influence on both men.[50]

Portraits

[edit]The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 fragmented the French art community. Many artists took refuge in England, joining Whistler, including Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet, while Manet and Degas stayed in France. Like Whistler, Monet and Pissarro both focused their efforts on views of the city, and it is likely that Whistler was exposed to the evolution of Impressionism founded by these artists and that they had seen his nocturnes.[51] Whistler was drifting away from Courbet's "damned realism" and their friendship had wilted, as had his liaison with Joanna Hiffernan.[52]

Whistler's Mother

[edit]

By 1871, Whistler returned to portraits and soon produced his most famous painting, the nearly monochromatic full-length figure entitled Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, but usually referred to as Whistler's Mother. A model failed to appear one day, according to a letter from his mother, so Whistler turned to his mother and suggested that he do her portrait. He had her stand at first, in his typically slow and experimental way, but that proved too tiring so the seated pose was adopted. It took dozens of sittings to complete.[53]

The austere portrait in his normally constrained palette is another Whistler exercise in tonal harmony and composition. The deceptively simple design is in fact a balancing act of differing shapes, particularly the rectangles of curtain, picture on the wall, and floor which stabilize the curve of her face, dress, and chair. Whistler commented that the painting's narrative was of little importance,[54] yet the painting was also paying homage to his pious mother. After the initial shock of her moving in with her son, she aided him considerably by stabilizing his behavior somewhat, tending to his domestic needs, and providing an aura of conservative respectability that helped win over patrons.[53]

The public reacted negatively to the painting, mostly because of its anti-Victorian simplicity during a time in England when sentimentality and flamboyant decoration were in vogue. Critics thought the painting a failed "experiment" rather than a work of art. The Royal Academy rejected it, but then grudgingly accepted it after lobbying by Sir William Boxall—but they hung it in an unfavorable location at their exhibition.[55]

From the start, Whistler's Mother sparked varying reactions, including parody, ridicule, and reverence, which have continued to today. Some saw it as "the dignified feeling of old ladyhood", "a grave sentiment of mourning", or a "perfect symbol of motherhood"; others employed it as a fitting vehicle for mockery. It has been satirized in endless variations in greeting cards and magazines, and by cartoon characters such as Donald Duck and Bullwinkle the Moose.[56] Whistler did his part in promoting the picture and popularizing the image. He frequently exhibited it and authorized the early reproductions that made their way into thousands of homes.[57] The painting narrowly escaped being burned in a fire aboard a train during shipping.[55] It was ultimately purchased by the French government, the first Whistler work in a public collection, and is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

During the Great Depression in the United States, the picture was billed as a "million dollar" painting and was a big hit at the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. It was accepted as a universal icon of motherhood by the worldwide public, which was not particularly aware of or concerned with Whistler's aesthetic theories. In recognition of its status and popularity, the United States issued a postage stamp in 1934 featuring an adaptation of the painting.[58]

In 2015, New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote that it "remains the most important American work residing outside the United States."[59] Martha Tedeschi writes:

Whistler's Mother, Wood's American Gothic, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa and Edvard Munch's The Scream have all achieved something that most paintings—regardless of their art historical importance, beauty, or monetary value—have not: they communicate a specific meaning almost immediately to almost every viewer. These few works have successfully made the transition from the elite realm of the museum visitor to the enormous venue of popular culture.[60]

Other portraits

[edit]

Other important portraits by Whistler include those of Thomas Carlyle (historian, 1873), Maud Franklin (his mistress, 1876), Cicely Alexander (daughter of a London banker, 1873), Lady Meux (socialite, 1882), and Théodore Duret (critic, 1884). In the 1870s, Whistler painted full-length portraits of his benefactor Frederick Leyland and his wife Frances. Leyland subsequently commissioned the artist to decorate his dining room (see Peacock Room below).[61]

Whistler had been disappointed over the irregular acceptance of his works for the Royal Academy exhibitions and the poor hanging and placement of his paintings. In response, Whistler staged his first solo show in 1874. The show was notable and noticed, however, for Whistler's design and decoration of the hall, which harmonized well with the paintings, in keeping with his art theories. A reviewer wrote, "The visitor is struck, on entering the gallery, with a curious sense of harmony and fitness pervading it, and is more interested, perhaps, in the general effect than in any one work."[62]

Whistler was not so successful a portrait painter as the other famous expatriate American John Singer Sargent. Whistler's spare technique and his disinclination to flatter his sitters, as well as his notoriety, may account for this. He also worked very slowly and demanded extraordinarily long sittings. William Merritt Chase complained of his sitting for a portrait by Whistler, "He proved to be a veritable tyrant, painting every day into the twilight, while my limbs ached with weariness and my head swam dizzily. 'Don't move! Don't move!' he would scream whenever I started to rest."[63] By the time he gained widespread acceptance in the 1890s, Whistler was past his prime as a portrait painter.[64]

Technique

[edit]Whistler's approach to portraiture in his late maturity was described by one of his sitters, Arthur J. Eddy, who posed for the artist in 1894:

He worked with great rapidity and long hours, but he used his colours thin and covered the canvas with innumerable coats of paint. The colours increased in depth and intensity as the work progressed. At first the entire figure was painted in greyish-brown tones, with very little flesh colour, the whole blending perfectly with the greyish-brown of the prepared canvas; then the entire background would be intensified a little; then the figure made a little stronger; then the background, and so on from day to day and week to week, and often from month to month. ... And so the portrait would really grow, really develop as an entirety, very much as a negative under the action of the chemicals comes out gradually—light, shadows, and all from the very first faint indications to their full values. It was as if the portrait were hidden within the canvas and the master by passing his wands day after day over the surface evoked the image.[65]

Printmaking

[edit]

Whistler produced numerous etchings, lithographs, and dry-points. His lithographs, some drawn on stone, others drawn directly on "lithographie" paper, are perhaps half as numerous as his etchings. Some of the lithographs are of figures slightly draped; two or three of the very finest are of Thames subjects—including a "nocturne" at Limehouse; while others depict the Faubourg Saint-Germain in Paris, and Georgian churches in Soho and Bloomsbury in London.[66]

The etchings include portraits of family, mistresses, and intimate street scenes in London and Venice.[68] Whistler gained an enormous reputation as an etcher. Martin Hardie wrote "there are some who set him beside Rembrandt, perhaps above Rembrandt, as the greatest master of all time. Personally, I prefer to regard them as the Jupiter and Venus, largest and brightest among the planets in the etcher's heaven."[69] He took great care over the printing of his etchings and the choice of paper. At the beginning and end of his career, he placed great emphasis on cleanness of line, though in a middle period he experimented more with inking and the use of surface tone.[70]

Butterfly signature and painting settings

[edit]Whistler's famous butterfly signature first developed in the 1860s out of his interest in Asian art. He studied the potter's marks on the china he had begun to collect and decided to design a monogram of his initials. Over time this evolved into the shape of an abstract butterfly. By around 1880, he added a stinger to the butterfly image to create a mark representing both his gentle, sensitive nature and his provocative, feisty spirit.[71] He took great care in the appropriate placement of the image on both his paintings and his custom-made frames. His focus on the importance of balance and harmony extended beyond the frame to the placement of his paintings to their settings, and further to the design of an entire architectural element, as in the Peacock Room.[48]

The Peacock Room

[edit]

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room[72] is Whistler's masterpiece of interior decorative mural art. Painted in 1876–1877, it is now considered a high example of the Anglo-Japanese style.

Frederick Leyland left the room in Whistler's care to make minor changes, "to harmonize" the room whose primary purpose was to display Leyland's china collection. He painted over the original paneled room designed by Thomas Jeckyll (1827–1881), in a unified palette of brilliant blue-greens with over-glazing and metallic gold leaf.[citation needed]

Whistler let his imagination run wild, however: "Well, you know, I just painted on. I went on—without design or sketch—putting in every touch with such freedom ... And the harmony in blue and gold developing, you know, I forgot everything in my joy of it." He completely painted over 16th-century Cordoba leather wall coverings first brought to Britain by Catherine of Aragon that Leyland had paid £1,000 for.[73]

Having acquired the centerpiece of the room, Whistler's painting of The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, American industrialist and aesthete Charles Lang Freer purchased the entire room in 1904 from Leyland's heirs, including Leyland's daughter and her husband, the British artist Val Prinsep. Freer then had the contents of the Peacock Room installed in his Detroit mansion. After Freer's death in 1919, The Peacock Room was permanently installed in the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. The gallery opened to the public in 1923.[74] A large painted caricature by Whistler of Leyland portraying him as an anthropomorphic peacock playing a piano, and entitled The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre – a pun on Leyland's miserliness and fondness for frilly shirt fronts – is in the permanent collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.[75]

Ruskin trial

[edit]In 1877 Whistler sued the critic John Ruskin after the critic condemned his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. Whistler exhibited the work in the Grosvenor Gallery, an alternative to the Royal Academy exhibition, alongside works by Edward Burne-Jones and other artists. Ruskin, who had been a champion of the Pre-Raphaelites and J. M. W. Turner, reviewed Whistler's work in his publication Fors Clavigera on July 2, 1877. Ruskin praised Burne-Jones, while he attacked Whistler:

For Mr. Whistler's own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay [founder of the Grosvenor Gallery] ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face.[76]

Whistler, seeing the attack in the newspaper, replied to his friend George Boughton, "It is the most debased style of criticism I have had thrown at me yet." He then went to his solicitor and drew up a writ for libel, which was served to Ruskin.[77] Whistler hoped to recover £1,000 plus the costs of the action. The case came to trial the following year after delays caused by Ruskin's bouts of mental illness, while Whistler's financial condition continued to deteriorate.[78] It was heard in the Exchequer Division of the High Court on November 25 and 26, 1878, before Baron Huddleston and a special jury.[79] Counsel for John Ruskin, Attorney General Sir John Holker, cross-examined Whistler:

Holker: "What is the subject of Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket?"

Whistler: "It is a night piece and represents the fireworks at Cremorne Gardens."

Holker: "Not a view of Cremorne?"

Whistler: "If it were A View of Cremorne it would certainly bring about nothing but disappointment on the part of the beholders. It is an artistic arrangement. That is why I call it a nocturne. ..."

Holker: "Did it take you much time to paint the Nocturne in Black and Gold? How soon did you knock it off?"

Whistler: "Oh, I 'knock one off' possibly in a couple of days – one day to do the work and another to finish it ..." [the painting measures 24 3/4 x 18 3/8 inches]

Holker: "The labour of two days is that for which you ask two hundred guineas?"

Whistler: "No, I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime."[80]

Detroit Institute of Arts

Whistler had counted on many artists to take his side as witnesses, but they refused, fearing damage to their reputations. The other witnesses for him were unconvincing and the jury's own reaction to the work was derisive. With Ruskin's witnesses more impressive, including Edward Burne-Jones, and with Ruskin absent for medical reasons, Whistler's counterattack was ineffective. Nonetheless, the jury reached a verdict in favor of Whistler, but awarded a mere farthing in nominal damages, and the court costs were split.[81] The cost of the case, together with huge debts from building his residence ("The White House" in Tite Street, Chelsea, designed with E. W. Godwin, 1877–8), bankrupted him by May 1879,[82] resulting in an auction of his work, collections, and house. Stansky[83] notes the irony that the Fine Art Society of London, which had organized a collection to pay for Ruskin's legal costs, supported him in etching "The Stones of Venice" (and in exhibiting the series in 1883), which helped recoup Whistler's costs.[citation needed]

Whistler published his account of the trial in the pamphlet Whistler v. Ruskin: Art and Art Critics,[84] included in his later The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890), in December 1878, soon after the trial. Whistler's grand hope that the publicity of the trial would rescue his career was dashed as he lost rather than gained popularity among patrons because of it. Among his creditors was Leyland, who oversaw the sale of Whistler's possessions.[85] Whistler made various caricatures of his former patron, including a biting satirical painting called The Gold Scab, just after Whistler declared bankruptcy. Whistler always blamed Leyland for his financial downfall.[86]

Later years

[edit]

"It is always a delight to remember that actually once Mr. Whistler was really shy! Those who had the pleasure of hearing his first Ten O'Clock must remember that when he came before his rather puzzled and distinguished audience, there were a few minutes of very palpable stage fright." – Anna Lea Merritt

The Life of James McNeill Whistler, by E. R. and J. Pennell, Volume 2 (1908)[88]

After the trial, Whistler received a commission to do twelve etchings in Venice. He eagerly accepted the assignment, and arrived in the city with girlfriend Maud Franklin, taking rooms in a dilapidated palazzo they shared with other artists, including John Singer Sargent.[89] Although homesick for London, he adapted to Venice and set about discovering its character. He did his best to distract himself from the gloom of his financial affairs and the pending sale of all his goods at Sotheby's. He was a regular guest at parties at the American consulate, and with his usual wit, enchanted the guests with verbal flourishes such as "the artist's only positive virtue is idleness—and there are so few who are gifted at it."[90]

His new friends reported, on the contrary, that Whistler rose early and put in a full day of effort.[91] He wrote to a friend, "I have learned to know a Venice in Venice that the others never seem to have perceived, and which, if I bring back with me as I propose, will far more than compensate for all annoyances delays & vexations of spirit."[92] The three-month assignment stretched to fourteen months. During this exceptionally productive period, Whistler finished over fifty etchings, several nocturnes, some watercolors, and over 100 pastels—illustrating both the moods of Venice and its fine architectural details.[89] Furthermore, Whistler influenced the American art community in Venice, especially Frank Duveneck (and Duveneck's "boys") and Robert Blum who emulated Whistler's vision of the city and later spread his methods and influence back to America.[93]

Back in London, the pastels sold particularly well, and he quipped, "They are not as good as I supposed. They are selling!"[94] He was actively engaged in exhibiting his other work but with limited success. Though still struggling financially, he was heartened by the attention and admiration he received from the younger generation of English and American painters who made him their idol and eagerly adopted the title "pupil of Whistler". Many of them returned to America and spread tales of Whistler's provocative egotism, sharp wit, and aesthetic pronouncements—establishing the legend of Whistler, much to his satisfaction.[94]

In January 1881, his mother Anna Whistler died. In her honour, he publicly adopted her maiden name McNeill as a middle name.[95]

Whistler published his first book, Ten O'Clock lecture in 1885, a major expression of his belief in "art for art's sake". At the time, the opposing Victorian notion reigned, namely, that art, and indeed much human activity, had a moral or social function. To Whistler, however, art was its own end and the artist's responsibility was not to society, but to himself, to interpret through art, and to neither reproduce nor moralize what he saw.[96] Furthermore, he stated, "Nature is very rarely right", and must be improved upon by the artist, with his own vision.[97]

Though differing with Whistler on several points, including his insistence that poetry was a higher form of art than painting,[98] Oscar Wilde was generous in his praise and hailed the lecture as a masterpiece:

not merely for its clever satire and amusing jests ... but for the pure and perfect beauty of many of its passages ... for that he is indeed one of the very greatest masters of painting, in my opinion. And I may add that in this opinion Mr. Whistler himself entirely concurs.[96]

Whistler, however, thought himself mocked by Oscar Wilde, and from then on, public sparring ensued leading to a total breakdown of their friendship, precipitated by a report written by Herbert Vivian.[99][100] Later, Wilde "symbolically murdered Whistler",[101] basing Basil Hallward, the murdered artist in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray on Whistler.[102]

Whistler joined the Society of British Artists in 1884, and on June 1, 1886, he was elected president. The following year, during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, Whistler presented to the Queen, on the Society's behalf, an elaborate album including a lengthy written address and illustrations that he made. Queen Victoria so admired "the beautiful and artistic illumination" that she decreed henceforth, "that the Society should be called Royal." This achievement was widely appreciated by the members, but soon it was overshadowed by the dispute that inevitably arose with the Royal Academy of Arts. Whistler proposed that members of the Royal Society should withdraw from the Royal Academy. This ignited a feud within the membership ranks that overshadowed all other society business. In May 1888, nine members wrote to Whistler to demand his resignation. At the annual meeting on June 4, he was defeated for re-election by a vote of 18–19, with nine abstentions. Whistler and 25 supporters resigned,[103] while the anti-Whistler majority (in his view) was successful in purging him for his "eccentricities" and "non-English" background.[104]

With his relationship with Maud Franklin unraveling, Whistler suddenly proposed to Beatrice Godwin (also called Beatrix or Trixie), a former pupil and the widow of his late friend, architect Edward William Godwin. Through his friendship with Godwin, Whistler had become close to Beatrice, whom Whistler painted in the full-length portrait titled Harmony in Red: Lamplight (GLAHA 46315).[105][106] By the summer of 1888 Whistler and Beatrice appeared in public as a couple. At a dinner Louise Jopling and Henry Labouchère insisted that they should be married before the end of the week.[107]

The marriage ceremony was quickly arranged; as a member of Parliament, Labouchère arranged for the Chaplain to the House of Commons to marry the couple.[107] No publicity was given to the ceremony to avoid the possibility of a furious Maud Franklin interrupting the marriage ceremony.[107] The marriage took place on August 11, 1888, with the ceremony attended by a reporter from the Pall Mall Gazette, so that the event received publicity. The couple left soon after for Paris, to avoid any risk of a scene with Maud.[107]

Whistler's reputation in London and Paris was rising and he gained positive reviews from critics and new commissions.[108] His book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies was published in 1890 with mixed success, but it afforded helpful publicity.[109]

In 1890, he met Charles Lang Freer, who became a valuable patron in America, and ultimately his most important collector.[110] Around this time, in addition to portraiture, Whistler experimented with early colour photography and with lithography, creating a series featuring London architecture and the human figure, mostly female nudes.[111] He contributed the first three of his Songs of Stone lithographs to The Whirlwind, a Neo-Jacobite magazine published by his friend Herbert Vivian.[112] Whistler had met Vivian in the late 1880s when both were members of the Order of the White Rose, the first of the Neo-Jacobite societies.[citation needed]

In 1891, with help from his close friend Stéphane Mallarmé, Whistler's Mother was purchased by the French government for 4,000 francs. This was much less than what an American collector might have paid, but that would not have been so prestigious by Whistler's reckoning.[113]

After an indifferent reception to his solo show in London, featuring mostly his nocturnes, Whistler abruptly decided he had had enough of London. He and Trixie moved to Paris in 1892 and resided at n° 110 Rue du Bac, Paris, with his studio at the top of 86 Rue Notre Dame des Champs in Montparnasse.[114][115]

He felt welcomed by his old Paris friends Monet, Auguste Rodin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as Stéphane Mallarmé, and he set himself up a large studio. He was at the top of his career when it was discovered that his wife Trixie had cancer. They returned to London in February 1896, taking rooms at the Savoy Hotel while they sought medical treatment. He made drawings on lithographic transfer paper of the view of the River Thames, from the hotel window or balcony, as he sat with her.[116] She died a few months later.[117]

In 1899, Charles Freer introduced Whistler to his friend and fellow businessman Richard Albert Canfield, who became a personal friend and patron of Whistler's. Canfield owned a number of fashionable gambling houses in New York and Rhode Island, including Saratoga Springs and Newport, and was also a man of culture with refined tastes in art. He owned early American and Chippendale furniture, tapestries, Chinese porcelain and Barye bronzes, and possessed the second-largest and most important Whistler collection in the world prior to his death in 1914.[citation needed]

In May 1901, Canfield commissioned a portrait from Whistler; he started to pose for Portrait of Richard A. Canfield (YMSM 547) in March 1902. According to Alexander Gardiner, Canfield returned to Europe to sit for Whistler at the New Year in 1903, and sat every day until May 16, 1903. Whistler was ill and frail at this time and the work was his last completed portrait. The deceptive air of respectability that the portrait gave Canfield caused Whistler to call it 'His Reverence'. The two men were in correspondence from 1901 until Whistler's death.[118] A few months before his own death, Canfield sold his collection of etchings, lithographs, drawings and paintings by Whistler to the American art dealer Roland F. Knoedler for $300,000. Three of Canfield's Whistler paintings hang in the Frick Museum in New York City.[citation needed]

In the final seven years of his life, Whistler did some minimalist seascapes in watercolor and a final self-portrait in oil. He corresponded with his many friends and colleagues. Whistler founded an art school in 1898, but his poor health and infrequent appearances led to its closure in 1901.[119] He died in London on July 17, 1903, six days after his 69th birthday.[120] He is buried in Chiswick Old Cemetery in west London, adjoining St Nicholas Church, Chiswick.[121]

Whistler was the subject of a 1908 biography by his friends, the husband-and-wife team of Joseph Pennell and Elizabeth Robins Pennell, printmaker and art critic respectively. The Pennells' vast collection of Whistler material was bequeathed to the Library of Congress.[122] The artist's entire estate was left to his sister-in-law Rosalind Birnie Philip. She spent the rest of her life defending his reputation and managing his art and effects, much of which eventually was donated to Glasgow University.[123]

Personal relationships

[edit]

Whistler had a distinctive appearance, short and slight, with piercing eyes and a curling mustache, often sporting a monocle and the flashy attire of a dandy.[124] He affected a posture of self-confidence and eccentricity. He often was arrogant and selfish toward friends and patrons. A constant self-promoter and egoist, he relished shocking friends and enemies. Though he could be droll and flippant about social and political matters, he always was serious about art and often invited public controversy and debate to argue for his strongly held theories.[3]

Whistler had a high-pitched, drawling voice and a unique manner of speech, full of calculated pauses. A friend said, "In a second you discover that he is not conversing—he is sketching in words, giving impressions in sound and sense to be interpreted by the hearer."[125]

Whistler was well known for his biting wit, especially in exchanges with his friend and rival Oscar Wilde. Both were figures in the Café society of Paris, and they were often the "talk of the town". They frequently appeared as caricatures in Punch, to their mutual amusement. On one occasion, young Oscar Wilde attended one of Whistler's dinners, and hearing his host make some brilliant remark, apparently said, "I wish I'd said that", to which Whistler riposted, "You will, Oscar, you will!" In fact, Wilde did repeat in public many witticisms created by Whistler.[96] Their relationship soured by the mid-1880s, as Whistler turned against Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement. When Wilde was publicly acknowledged to be a homosexual in 1895, Whistler openly mocked him.[citation needed]

Whistler reveled in preparing and managing his social gatherings. As a guest observed:

One met all the best in Society there—the people with brains, and those who had enough to appreciate them. Whistler was an inimitable host. He loved to be the Sun round whom we lesser lights revolved ... All came under his influence, and in consequence no one was bored, no one dull.[126]

In Paris, Whistler was friends with members of the Symbolist circle of artists, writers and poets that included Stéphane Mallarmé[127] and Marcel Schwob.[128] Schwob had met Whistler in the mid-1890s through Stéphane Mallarmé; they had other mutual friends, including Oscar Wilde (until they argued) and Whistler's brother-in-law, Charles Whibley.

Whistler was friendly with many French artists, including Henri Fantin-Latour, Alphonse Legros, and Gustave Courbet. He illustrated the book Les Chauves-Souris with Antonio de La Gandara. He also knew Édouard Manet and the Impressionists, notably Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas. As a young artist, he was a close friend of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His close friendships with Monet and poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who translated the Ten O'Clock lecture into French, helped strengthen respect for Whistler by the French public.[129] Whistler was friendly with his fellow students at Gleyre's studio, including Ignace Schott, whose son Leon Dabo Whistler later would mentor.[130]

Whistler's lover and model for The White Girl, Joanna Hiffernan, also posed for Gustave Courbet. Historians speculate that Courbet used her as the model for his erotic paintings Le Sommeil and L'Origine du monde, possibly leading to the breakup of the friendship between Whistler and Courbet.[131]

During the 1870s and much of the 1880s, he lived with his model and mistress Maud Franklin. Her ability to endure long, repetitive sittings helped Whistler develop his portrait skills.[126] He not only made several excellent portraits of her, but she was also a helpful stand-in for other sitters. Whistler had two daughters by Maud Franklin: Ione (born circa 1877) and Maud McNeill Whistler Franklin (born 1879).[132] Maud sometimes referred to herself as 'Mrs. Whistler',[133] and in the census of 1881 gave her name as 'Mary M. Whistler'.[134]

Whistler had several extramarital children, of whom Charles James Whistler Hanson (1870–1935) is the best documented.[135] After Whistler parted from his mistress Joanna Hiffernan, she helped to raise Hanson, even though his mother was the parlour maid, Louisa Fanny Hanson.[136][137]

In 1888, Whistler married Beatrice Godwin, whom he called Beatrix or Trixie. She was the widow of his friend E. W. Godwin, the architect who had designed Whistler's White House, and the daughter of the sculptor John Birnie Philip[138] and his wife Frances Black. Beatrix and her sisters Rosalind Birnie Philip[139] and Ethel Whibley posed for many of Whistler's paintings and drawings; with Ethel Whibley modeling for Mother of Pearl and Silver: The Andalusian (1888–1900).[137] The first five years of their marriage were very happy, but her later life was a time of misery for the couple, due to her illness and eventual death from cancer. Near the end, she lay comatose much of the time, completely subdued by morphine, given for pain relief. Her death was a heavy blow Whistler never quite overcame.[140]

Legacy

[edit]

Whistler was inspired by and incorporated many sources in his art, including the work of Rembrandt, Velázquez, and ancient Greek sculpture to develop his own highly influential and individual style.[71] He was adept in many media, with over 500 paintings, as well as etchings, pastels, watercolors, drawings, and lithographs.[141] Whistler was a leader in the Aesthetic Movement, promoting, writing, and lecturing on the "art for art's sake" philosophy. With his pupils, he advocated simple design, economy of means, the avoidance of over-labored technique, and the tonal harmony of the final result.[71]

Whistler has been the subject of many major museum exhibitions, studies, and publications. Like the Impressionists, he employed nature as an artistic resource. Whistler insisted that it was the artist's obligation to interpret what he saw, not be a slave to reality, and to "bring forth from chaos glorious harmony".[71]

During his life, he influenced many artists throughout the English-speaking world. Whistler had significant contact and exchanged ideas and ideals with Realist, Impressionist, and Symbolist painters. The artist Walter Sickert was his pupil,[142] and the writer Oscar Wilde was his friend. His Tonalism had a profound effect on many American artists, including John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase, Henry Salem Hubbell, Willis Seaver Adams (whom he befriended in Venice) and Arthur Frank Mathews, whom Whistler met in Paris in the late 1890s and who took Whistler's Tonalism to San Francisco, spawning a broad use of that technique among turn-of-the-century California artists. Whistler was also a major influence on the 1880s Heidelberg School movement in Australia, otherwise known as Australian impressionism.[143] As American critic Charles Caffin wrote in 1907:

He did better than attract a few followers and imitators; he influenced the whole world of art. Consciously or unconsciously, his presence is felt in countless studios; his genius permeates modern artistic thought.[3]

During a fourteen-month stay in Venice in 1879 and 1880, Whistler created a series of etchings and pastels that not only reinvigorated his finances (this was after he had declared bankruptcy following the Ruskin trial), but also re-energized the way in which artists and photographers interpreted the city—focusing on the back alleys, side canals, entrance ways, and architectural patterns—and capturing the city's unique atmospherics.[93]

Honored on Issue of 1940

In 1940 Whistler was commemorated on a United States postage stamp when the U.S. Post Office issued a set of 35 stamps commemorating America's famous authors, poets, educators, scientists, composers, artists, and inventors: the Famous Americans Series.[citation needed]

The Gilbert and Sullivan operetta Patience pokes fun at the Aesthetic movement, and the lead character of Reginald Bunthorne is often identified as a send-up of Oscar Wilde, though Bunthorne is more likely an amalgam of several prominent artists, writers, and Aesthetic figures. Bunthorne wears a monocle and has prominent white streaks in his dark hair, as did Whistler.[citation needed]

Novelist Henry James "had become well enough acquainted with Whistler to base several fictional characters on the 'queer little Londonized Southerner,' most notably in Roderick Hudson and The Tragic Muse".[144] Whistler "also appeared as one of Henry James's most attractive minor characters, the sculptor Gloriani in The Ambassadors, whose personality, way of life, and even home are closely based on Whistler."[145]

George du Maurier's 1894 novel Trilby has a character, Joe Sibley, "the idle apprentice," who was meant to depict Whistler.[146][147] "Whistler threatened to sue, and in subsequent editions the character was replaced by another."[148] Whistler was also the model for a character in Marcel Proust's novel, In Search of Lost Time — the painter Elstir.[149][145]

Whistler was the favorite artist of singer and actress Doris Day. She owned and displayed an original etching of Whistler's Rotherhithe and two of his original lithographs, The Steps, Luxembourg Gardens, Paris and The Pantheon, from the Terrace of the Luxembourg Gardens.[150]

The Lowell, Massachusetts, house in which Whistler was born is now preserved as the Whistler House Museum of Art. He is buried at St Nicholas Church, Chiswick.[citation needed]

Honors

[edit]Whistler achieved worldwide recognition during his lifetime:

- 1884: elected an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

- 1892: made an officer of the Légion d'honneur in France.[151]

- 1898: became a charter member and first president, International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers.

A statue of James McNeill Whistler by Nicholas Dimbleby was erected in 2005 at the north end of Battersea Bridge on the River Thames in the United Kingdom.[152]

Gallery

[edit]-

Rotherhithe

1860

etching on paper -

The Thames in Ice

1860

oil on canvas -

The Princess from the Land of Porcelain

1863–1865

oil on canvas -

Three Figures, Pink and Grey

1868–1878

oil on canvas -

Variations in Pink and Grey- Chelsea

1870–1871

oil on canvas -

Nocturne in Gray and Gold, Westminster Bridge

1874

oil on canvas -

Nocturne

1870–1877

oil on canvas -

The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre

1879

oil on canvas -

Fishing Boat

1879–1880

etching on laid paper -

Nocturne in Pink and Gray, Portrait of Lady Meux

1881

oil on canvas -

Amsterdam Nocturne

1883–1884

watercolour on brown paper -

An Orange Note

1884

oil on wood -

Green and Silver- Beaulieu, Touraine

1888

watercolor on linen -

The Canal Amsterdam

1889

oil on wood -

The Bathing Posts, Brittany

1893

oil on wood -

Harmony in Blue and Gold - The Little Blue Girl

1894–1902

oil on canvas -

Blue and Coral The Little Blue Bonnet

1898

oil on canvas -

Green and Violet, Mrs. Walter Sickert oil on canvas

Auction records

[edit]On October 27, 2010, Swann Galleries set a record price for a Whistler print at auction, when Nocturne, an etching and drypoint printed in black on warm, cream Japan paper, 1879–80 sold for $282,000.[153]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bridgers, Jeff (June 20, 2013). "Whistler's Butterfly" (webpage). Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Image gallery of some of Whistler's well-known paintings and others by his contemporaries". Dia.org. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Peters (1996), p. 4.

- ^ Spencer, Robin (2004). "Whistler, James Abbott Mc Neill (1834–1903), painter and printmaker". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36855. ISBN 9780198614128. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Letter to Whistler from Anna Matilda Whistler, dated July 11, 1855. The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, Glasgow University Library, reference MS Whistler W458 Archived July 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Letter to Whistler from Anna Matilda Whistler, dated July 11, 1876. The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, Glasgow University Library, reference Whistler W552. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ a b "James Abbott McNeill Whistler – Questroyal". www.questroyalfineart.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ a b New England Magazine (February 1904). "Whistler's Father". New England Magazine. 29. Boston, MA: America Company.

- ^ "Home". www.whistlerhouse.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c Peters (1996), p. 11.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 9.

- ^ Phaneuf, Wayne (May 10, 2011). "Springfield's 375th: From Puritans to presidents". masslive.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "Springfield Museums". Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 11.

- ^ Robin Spencer, ed., Whistler: A Retrospective, Wings Books, New York, 1989, p. 35, ISBN 0-517-05773-5

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 20.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 18-20.

- ^ Kunitz, Stanley (1938). American Authors, 1600-1900: A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature. New York: H.W. Wilson. p. 802.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Peters (1996), p. 12.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 24.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), pp. 26–27.

- ^ "Books: West Pointer with a Brush". Time. March 23, 1953. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Blackwell, Jon, A Salute to West Point". Usma.edu. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 35.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 36.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 38.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 47.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 50.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 52.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 60.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 48.

- ^ a b Peters (1996), p. 13.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 90.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 14.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 15.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 106, 119.

- ^ "Explanation of Whistler's purpose in making the painting Symphony in White". Dia.org. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 17.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 18, 24.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 19.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 141.

- ^ "Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea Pages 102–106 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". British History Online. Victoria County History, 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 30.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 187.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 186.

- ^ "Detroit Institute of Arts webpage image and description of painting". Dia.org. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 191.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 192.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 194.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 179.

- ^ Anderson and Koval, p. 141, plate 7.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 180.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 34.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 183.

- ^ Margaret F. MacDonald, ed., Whistler's Mother: An American Icon, Lund Humphries, Burlington, Vt., 2003, p. 137; ISBN 0-85331-856-5

- ^ Margaret F. MacDonald, p. 125.

- ^ Margaret F. MacDonald, p. 80.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (March 3, 2017). "She's ba-aack: 'Whistler's Mother,' a more exciting painting than you might think, returns to Art Institute". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ MacDonald, p. 121.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 36, 43.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 197.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 275.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 199.

- ^ Spencer, Robin, Whistler, p. 132. Studio Editions Ltd., 1994; ISBN 1-85170-904-5

- ^ Wedmore 1911, p. 596.

- ^ "The Doorway". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 311.

- ^ Hardie (1921), p. 18.

- ^ Hardie (1921), pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d Peters (1996), p. 7.

- ^ "A Closer Look – James McNeill Whistler – Peacock Room". Asia.si.edu. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 37.

- ^ "Freer Gallery, The Peacock Room". Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "FRAME|WORK: The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre (The Creditor) by James McNeill Whistler". Deyoung.famsf.org. May 30, 2012. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 215.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 216.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 217.

- ^ Whistler, 2–5; The Times (London, England), Tuesday, November 26, 26, 1878; p. 9.

- ^ Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Nineteenth-Century European Art, p. 349.

- ^ Peters, pp. 51–52.

- ^ "See The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler". Whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. October 14, 2003. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Peter Stansky's review of Linda Merrill's A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Winter, 1994), pgs. 536–7 [1] Archived May 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whistler, James Mcneill (January 1967). The Gentle Art of Making Enemies – James McNeill Whistler. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486218755. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 227.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 210.

- ^ "National Gallery of Art webpage describing Mother of pearl and silver: The Andalusian". Nga.gov.au. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ "Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 1908. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 228.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 230.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 232.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Peters (1996), p. 54.

- ^ a b Peters (1996), p. 55.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 242.

- ^ a b c Peters (1996), p. 57.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 256.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 270.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 271.

- ^ Ellmann, Richard (September 4, 2013). Oscar Wilde. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780804151122.

- ^ Sutherland (2014), p. 241.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 314.

- ^ Margaret F. McDonald, "Whistler for President!", in Richard Dorment and Margaret F. McDonald, eds., James McNeill Whistler, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994, pp. 49–55, ISBN 0-89468-212-1

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 273.

- ^ ""Harmony in Red: Lamplight" (1884–1886)". The Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Weintraub (1974), p. 323.

- ^ a b c d Weintraub (1974), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Weintraub (1974), pp. 308–373.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 60.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 321.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 324.

- ^ Sutherland (2014), p. 247.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 342.

- ^ Weintraub (1974), pp. 374–384.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 357.

- ^ "Turner, Whistler, Monet: Thames Views" Archived March 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. The Tate Museum, London, 2005, accessed December 3, 2010.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 62-63.

- ^ "The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler". www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Peters (1996), p. 63.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 457.

- ^ London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer, by Hugh Meller and Brian Parsons.

- ^ Anderson and Koval, plate 44.

- ^ Anderson and Koval, plate 46.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 240.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 204.

- ^ a b Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 203.

- ^ Letter from James McNeill Whistler to Beatrix Whistler, March 3, 1895, University of Glasgow, Special Collections, reference: GB 0247 MS Whistler W620.

- ^ "University of Glasgow, Special Collections". Whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 289.

- ^ Pennell & Pennell (1911), p. 43.

- ^ Sutherland (2014), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Spencer, p. 88.

- ^ Weintraub (1974), pp. 166 & 322.

- ^ "Biography – Maud Franklin, 1857–1941". The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler. University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on July 25, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Anderson and Koval, plate 40.

- ^ Patricia de Montfort, "White Muslin: Joanna Hiffernan and the 1860s," in Whistler, Women, and Fashion (Frick Collection, New York, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003), p. 79.

- ^ a b "Biography of Ethel Whibley (1861–1920) University of Glasgow, Special Collections". Whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. May 21, 1920. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler :: Biography". Whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. February 20, 2003. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Biography of Rosalind Birnie Philip, (1873–1958) University of Glasgow, Special Collections". Whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Anderson and Koval, plate 45.

- ^ Anderson & Koval (1995), p. 106.

- ^ Sickert worked hard with Whistler on his "Ten O'Clock" lecture. Sturgis, Matthew, Walter Sickert: A Life, HarperCollins, 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Heidelberg School Archived February 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, emelbourne.net.au. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Sutherland (2014), p. 268.

- ^ a b Dorment and MacDonald, Whistler, p. 22.

- ^ "Bonhams : DU MAURIER, GEORGE. 1834-1896. Trilby in Harper's New Monthly Magazine. New York Harper & Brothers, January-August 1894". www.bonhams.com.

- ^ "Whistler Etchings :: Biography". etchings.arts.gla.ac.uk.

- ^ Golding, John, "Supreme Outsider," The New York Review, May 25, 1995

- ^ Dorment, Richard, "Venice Out of Season," The New York Review of Books, October 24, 1991.

- ^ "Doris Day's Estate at Auction". Barnebys.com. April 1, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Léonore database". Culture.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Cookson 2006, p. 122.

- ^ "Nocturne: Our Most Expensive Print". Swann Galleries. October 29, 2010. Archived from the original on August 16, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

References

[edit]- Anderson, Ronald; Koval, Anne (1995). James McNeill Whistler: Beyond the Myth. New York, NY.: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-0187-2. OCLC 613244627.; London: John Murray, 1994. ISBN 978-0-7195-5027-0

- Cookson, Brian (2006), Crossing the River, Edinburgh: Mainstream, ISBN 978-1-84018-976-6, OCLC 63400905

- Hardie, Martin (1921). The British School of Etching. London: The Print Collectors Club.

- Pennell, Joseph; Pennell, Elizabeth Robins (1911). The Life of James McNeill Whistler (5th ed.). London: William Heinemann.

- Peters, Lisa N. (1996). James McNeill Whistler. New York, NY: Smithmark. ISBN 978-0-7651-9961-4. OCLC 36587931. Also published New York: Todtri Productions Limited. ISBN 1-880908-70-0.

- Snodin, Michael and John Styles. Design & The Decorative Arts, Britain 1500–1900. V&A Publications: 2001. ISBN 1-85177-338-X

- Spencer, Robin (1994). Whistler. London: Studio Editions. ISBN 1-85170-904-5

- Sutherland, Daniel E. (2014). Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13545-9.

- Wedmore, Frederick (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 596–597.

- Weintraub, Stanley (1974). Whistler: A Biography. New York, NY: Weybright and Talley. ISBN 0-679-40099-0.

Primary sources

[edit]- "George A. Lucas Papers". The Baltimore Museum of Art. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015.

- Thorp, Nigel, ed. Whistler on Art: Selected Letters and Writings of James McNeill Whistler. Manchester: Carcanet Press; Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994. Includes "Ten O'Clock", pp. 79–95, and extracts from press reviews of it, pp. 95–102.

- Whistler, James Abbott McNeill, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies 3rd ed., G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1904 [1890].

- Wilde, Oscar (February 21, 1885). "Mr Whistler’s Ten O’Clock"

Further reading

[edit]- Bendix, Deanna Marohn (1995). Diabolical Designs: Paintings, Interiors, and Exhibitions of James McNeill Whistler. Washington D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-415-5.

- Berman, Avis (1993). James McNeill Whistler: First Impressions. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3968-1.

- Corbacho, Henri-Pierre (2018). A Short Biography of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Carlisle, Massachusetts: Benna Books. ISBN 978-1-944038-43-4.

- Cox, Devon (2015). The Street of Wonderful Possibilities: Whistler, Wilde & Sargent in Tite Street. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 9780711236738.

- Curry, David Park (1984). James McNeill Whistler at the Freer Gallery of Art. New York: W. W. Norton and Freer Gallery of Art. ISBN 9780393018479.

- Denker, Eric (2003). Whistler and His Circle in Venice. London: Merrell Publishers. ISBN 1-85894-200-4.

- Dorment, Richard, and MacDonald, Margaret F. (1994). James McNeill Whistler. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 1-85437-145-2. With contributions by Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., Ruth Fine, Geneviève Lacambre.

- Fleming, Gordon H. (1991). James Abbott McNeill Whistler: A Life. Adlestrop: Windrush. ISBN 0-900075-61-9..

- Fleming, Gordon H. (1978). The Young Whistler, 1834–66. London: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-04-927009-5..

- Glazer, Lee, et al. (2008). James McNeill Whistler in Context. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-934686-09-9.

- Glazer, Lee and Merrill, Linda, eds. (2013). Palaces of Art: Whistler and the Art Worlds of Aestheticism. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. ISBN 978-1-935623-29-8.

- Gregory, Horace (1961). The World of James McNeill Whistler. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-04-927009-5.

- Grieve, Alastair (1984). Whistler's Venice. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08449-8.

- Heijbroek, J. E. and MacDonald, Margaret F. (1997). Whistler and Holland. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. ISBN 90-400-9183-8.

- Honour, Hugh, and Fleming, John (1991). The Venetian Hours of Henry James, Whistler, and Sargent. Bulfinch Press/Little Brown.

- Laver, James (1930). Whistler. New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation.

- Levy, Mervyn, ed. (1975). Whistler Lithographs: An Illustrated Catalogue Raisonné. London: Jupiter Books.

- Lochnan, Katherine A.(1984). The Etchings of James McNeill Whistler. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03283-8.

- MacDonald Margaret F. (2001). Palaces in the Night: Whistler and Venice. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23049-3.

- MacDonald, Margaret F., ed. (2003). Whistler's Mother: An American Icon. Aldershot: Lund Humphries. ISBN 0-85331-856-5.

- MacDonald, Margaret F., Galassi, Susan Grace and Ribeiro, Aileen (2003). Whistler, Women, & Fashion. Frick Collection/Yale University. ISBN 0-300-09906-1.

- MacDonald, Margaret F., and de Montfort, Patricia (2013). An American in London: Whistler and the Thames. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78130-022-0.

- MacDonald, Margaret F., et al. (2020). The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art and London: Royal Academy of Arts/ Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25450-1.

- McCann, Justin, ed. (2015). Whistler and the World: The Lunder Collection of James McNeill Whistler. Waterville, Maine: Colby College Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0972848411.

- Merrill, Linda (1992). A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-300-0.

- Merrill, Linda (1998). The Peacock Room: A Cultural Biography. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art / Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07611-8.

- Merrill, Linda, and Ridley, Sarah (1993) The Princess and the Peacocks or, The Story of the [Peacock] Room. New York: Hyperion Books for Children, in association with the Freer Gallery of Art. ISBN 1-56282-327-2.

- Merrill, Linda, et al. (2003) After Whistler: The Artist and His Influence on American Painting. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10125-2.

- Munhall, Edgar (1995). Whistler and Montesquiou: The Butterfly and the Bat. New York and Paris: The Frick Collection/Flammarion. ISBN 2-08013-578-3.

- Murphy, Paul Thomas (2023). Falling Rocket: James Whistler, John Ruskin, and the Battle for Modern Art. New York: Pegasus Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-63936-491-6.

- Pearson, Hesketh (1978) [1952]. The Man Whistler. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 0-354-04224-6.

- Petri, Grischka (2011). Arrangement in Business: The Art Markets and the Career of James McNeill Whistler. Hildesheim: G. Olms. ISBN 978-3-487-14630-0.

- Robins, Anna Gruetzner (2007). A Fragile Modernism: Whistler and His Impressionist Followers. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13545-9.

- Spaulding, Frances (2nd ed. 1994 [1979]). Whistler. London and New York: Phaidon Press.

- Spencer, Robin (1991). Whistler: A Retrospective. New York: Wing Books. ISBN 0-517-05773-5.

- Stubbs, Burns A. (1950). James McNeill Whistler: A Biographical Outline Illustrated from the Collections of the Freer Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Sutherland, Daniel E. and Toutziari, Georgia (2018). Whistler's Mother: Portrait of an Extraordinary Life. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300229684.

- Sutton, Denys (1966). James McNeil Whistler: Paintings, Etchings, Pastels & Watercolours. London: Phaidon Press.

- Thompson, Jennifer A. (2017). "Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (cat. 1112)[permanent dead link]." In The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works[permanent dead link], edited by Christopher D. M. Atkins. A Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication. ISBN 978-0-87633-276-4.

- Twohig, Edward (2018). Print REbels: Haden, Palmer, Whistler and the Origins of the RE (Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers). London: Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers. ISBN 978-1-5272-1775-1.

- Taylor, Hilary (1978). James McNeill Whistler. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 0-289-70836-2.

- Walden, Sarah (2003). Whistler and His Mother: An Unexpected Relationship: Secrets of an American Masterpiece. London: Gibson Square; Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 1903933285.

- Walker, John (1987). James McNeill Whistler. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in association with The National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0810917866.

- Young, Andrew McLaren; MacDonald, Margaret; Spencer, Robin; with the assistance of Hamish Miles (1980). The Paintings of James McNeill Whistler. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02384-7.

External links

[edit]- 111 artworks by or after James McNeill Whistler at the Art UK site

- Works by James McNeill Whistler at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James McNeill Whistler at the Internet Archive

- Works by James McNeill Whistler at Open Library

- The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, Glasgow University Edited by M.F. MacDonald, P.de Montfort, N. Thorp.

- Catalogue raisonné of the etchings of James McNeill Whistler Archived April 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine by M.F. MacDonald, G. Petri, M. Hausberg, J. Meacock.

- James McNeill Whistler: The Paintings, a Catalogue Raisonné, University of Glasgow, 2014 by M.F. MacDonald, G. Petri.

- James McNeill Whistler exhibition catalogs

- The Freer Gallery of Art which houses the premier collection of Whistler works including the Peacock Room.

- An account of the Whistler/Ruskin affair

- Whistler House Museum of Art official web site

- Works by James Abbott McNeill Whistler Archived April 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine at University of Michigan Museum of Art

- Rudolf Wunderlich Collection of James McNeill Whistler Exhibition Catalogs at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "James McNeill Whistler," poem by Florence Earle Coates

- "Whistler, James Abbott McNeill". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Whistler, James Abbott McNeill". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- The Whistler Society, London. Founded 2012.

- Jennifer A. Thompson, "Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (cat. 1112)"[permanent dead link] in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works[permanent dead link], a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.